Photography

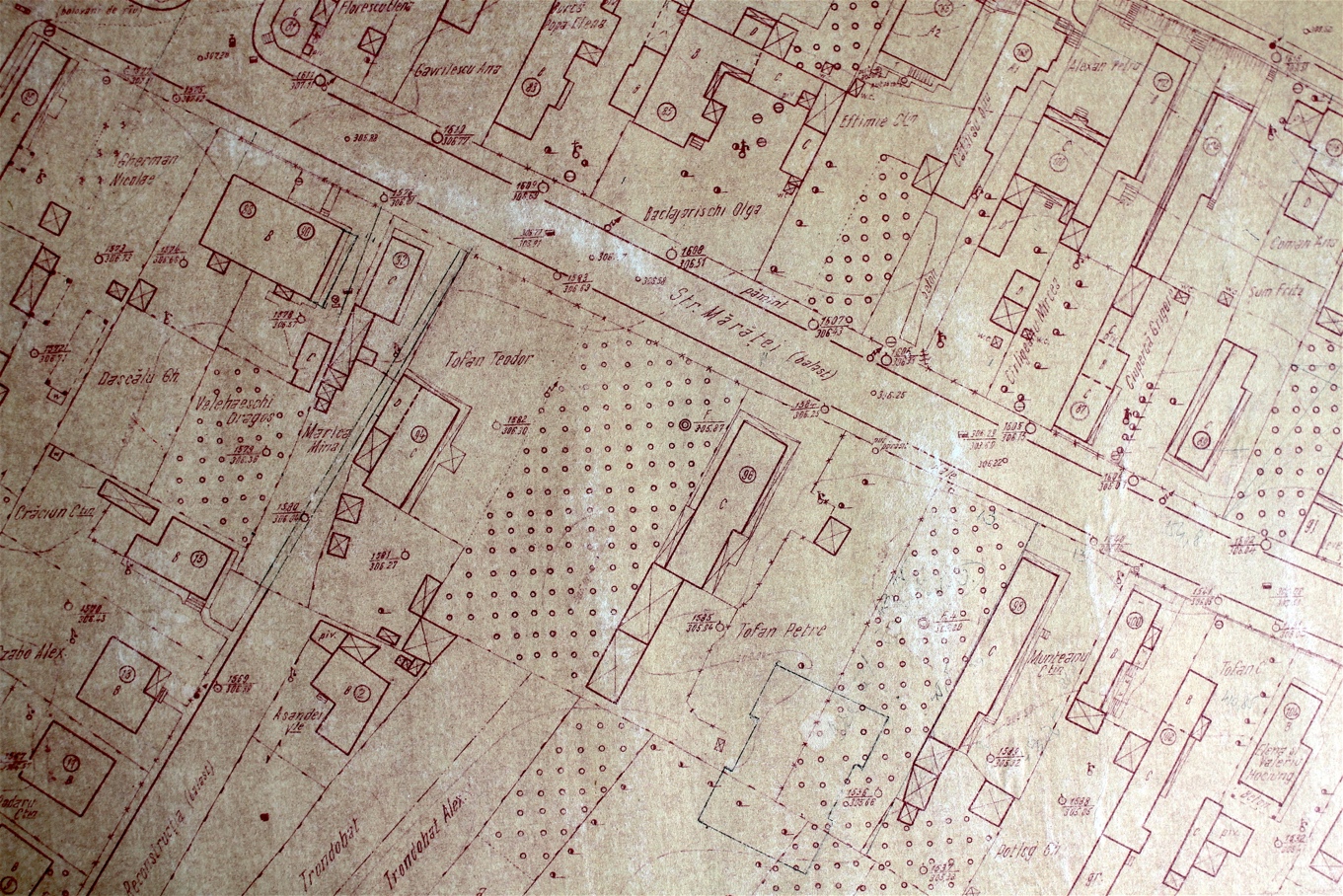

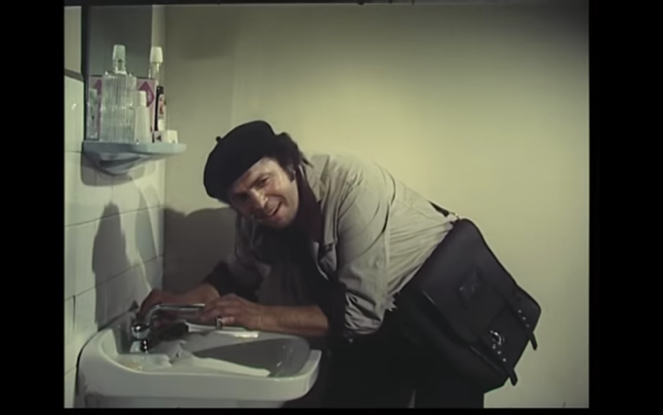

I engaged in numerous other exercises of visual elicitation with the inhabitants who participated in my research, utilising photographs, maps, drawings, etc. Such a collaborative approach broke the before-mentioned boundaries of suspicion towards myself as a researcher. The research method of photo-elicitation has been considered collaborative, because it is a “dialogue based on the authority of the subject rather than the researcher” (Harper, 2002, p. 68). Apart from acknowledging that the meaning of photographs resides in the discursive practices that constitute them, Harper states that the meaning of the photograph is also constructed by the maker and the viewer (thus both in the production and the consumption stage), “both of whom carry their social position and interest of the photographic act” (Harper, 2002, p. 70).

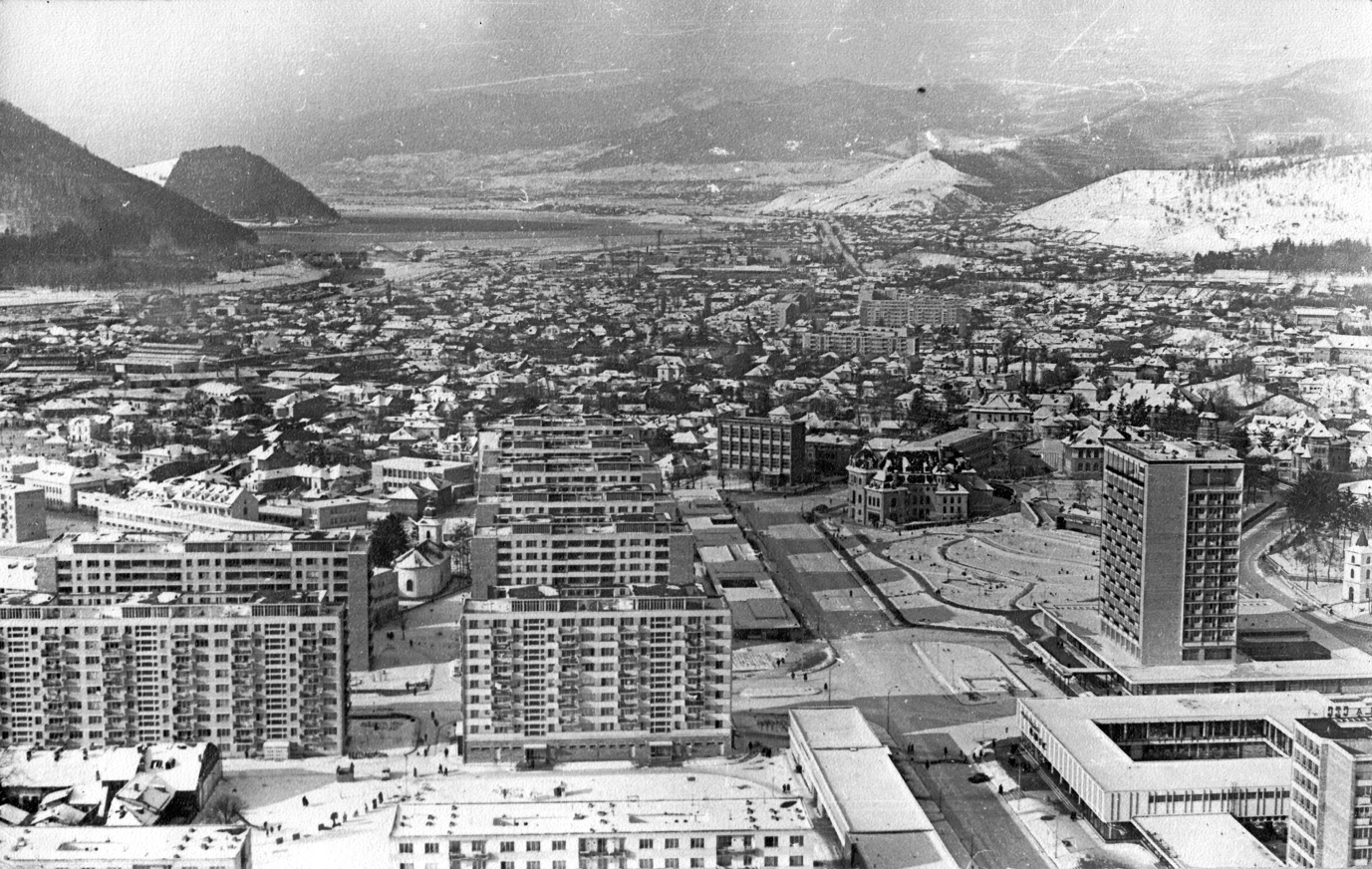

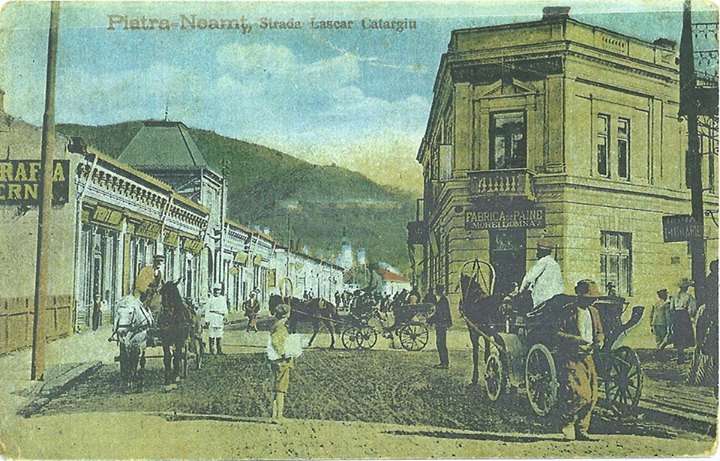

The photographs used in visual elicitation came from multiple sources: my own photographs, participants’ photographs and archival photographs. Having trained as a professional photographer at State University of New York and as a visual anthropologist at the University of Oxford, I am used to using my camera for the purpose of documentation. I therefore took photographs of the city during extensive walks, so that I would attentively notice the elements of material culture that seemed to occupy important parts in inhabitants’ experiences of living in a block of flats: staircases, windows, balconies, playgrounds, heating systems, churches, stores, plants, pigeons, etc. I thus built a large collection of contemporary images (approx. 2000) which could inform my research, and could be shared with my research participants (see Project for a selection my photographs).

After editing my photographs and analysing them in great detail while taking notes of the most poignant details, I would create a new set of themes that I wanted to discuss with my research participants (for instance, the different materials used to close off balconies). This not only allowed me to rely on my participants for the learning process, but also to become immersed in the city and to analyse it very closely. Indeed, a photograph “can’t reveal ultimate truths, but it can ‘reveal’ a particular openness to the visible world in ways that permit access to new and surprising aspects” (Barnouw, 1994, p. 238).

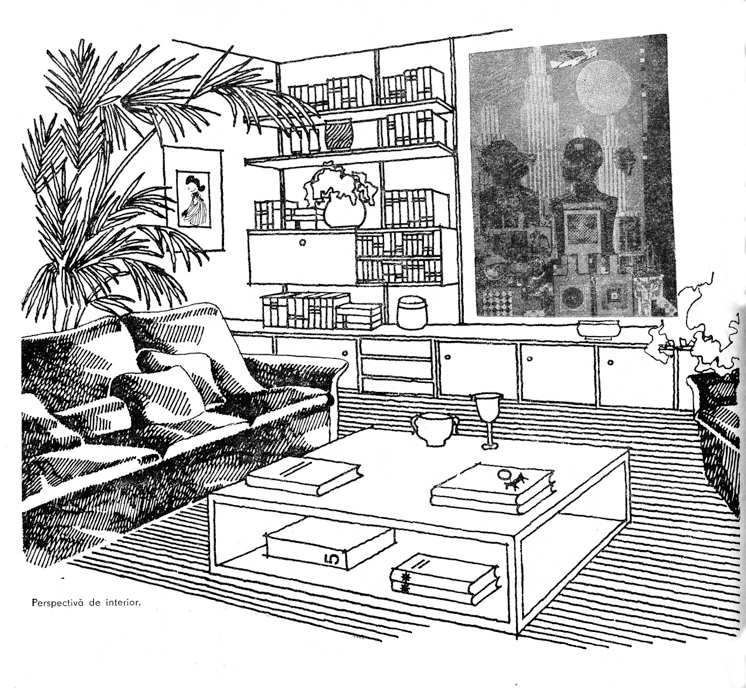

Apart from photographs, I collected other visual and linguistic materials to share with my research participants. I did a detailed survey of the Ceahlăul local newspaper archives around the time in which the H2B block was built — between 1970 and 1976 — to pick up on the discourse before and after their construction, but also on the initial engagements with these blocks of flats. Additionally, my research participants pointed me in the direction of an original source of information: home magazines from the socialist period, such as the Femeia (The Woman) Magazine (1970-1988), or education books for women, such as Cartea Tinerelor Gospodine (The Book of Young Housewives, 1987) or Gospodina si Oaspetii Familiei (The Housewife and the Family Guests, 1981). These painted a vivid picture of socialist ideals of the home, and informed the aesthetic of many of my research participants, still being extensively used in many households.

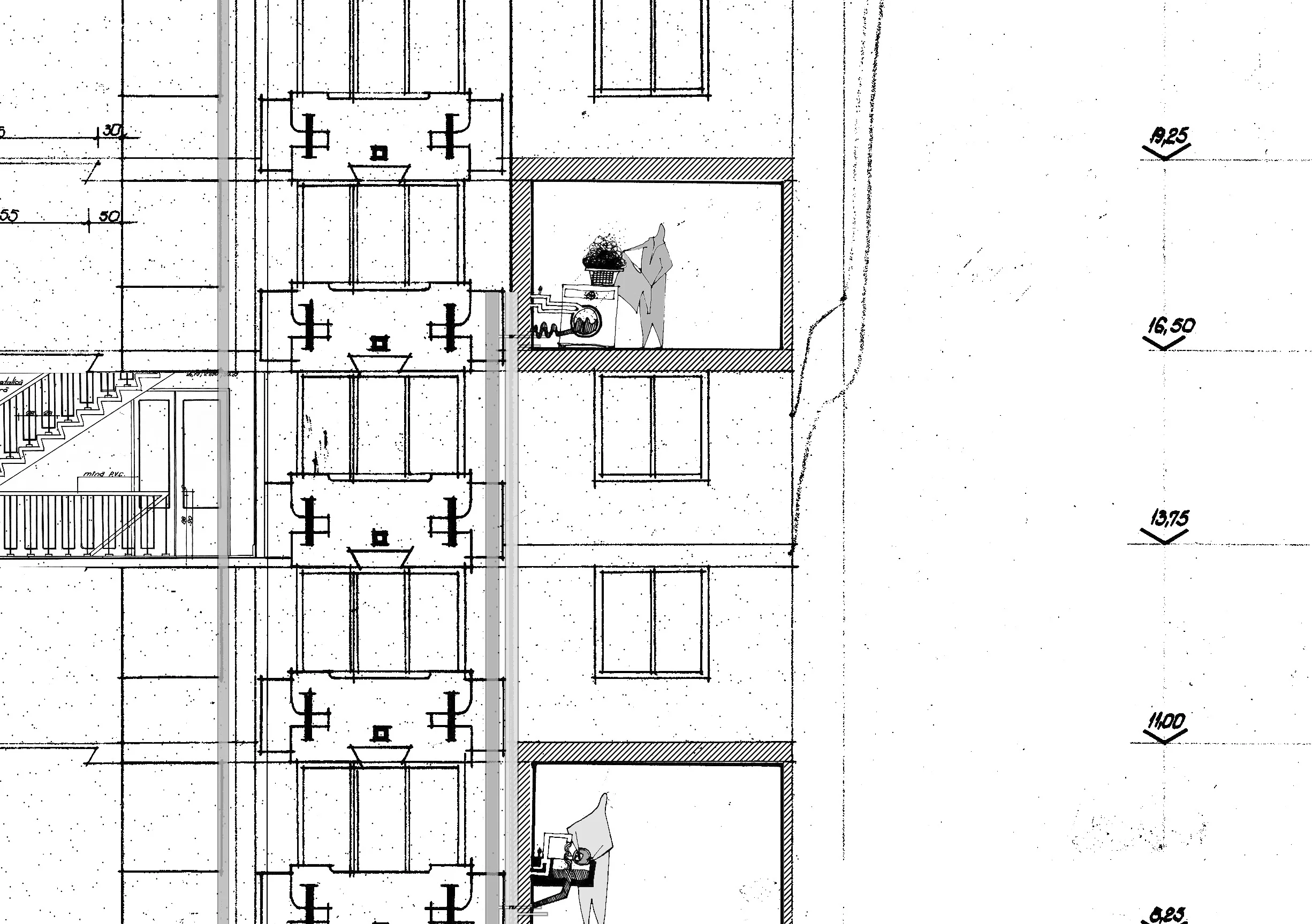

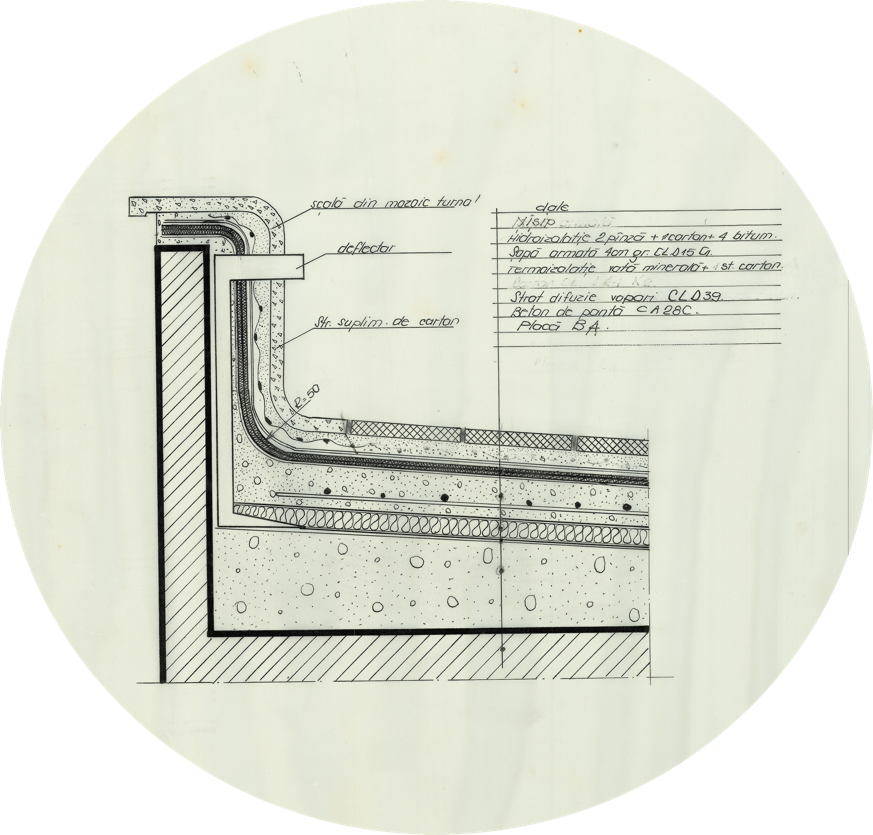

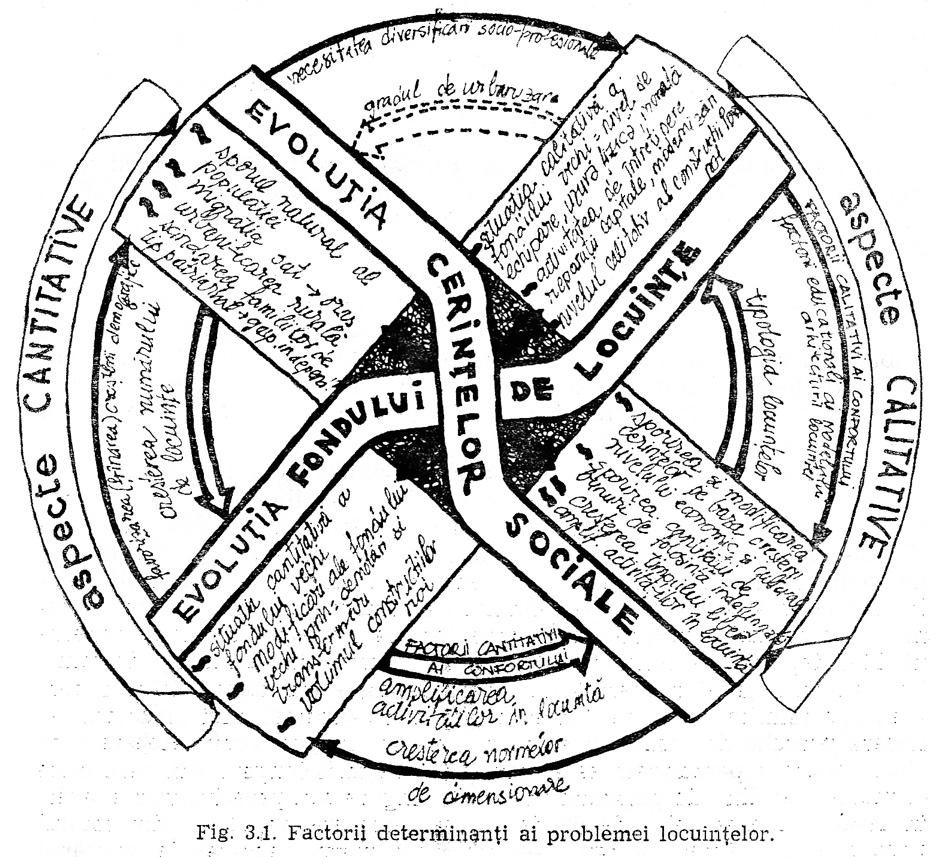

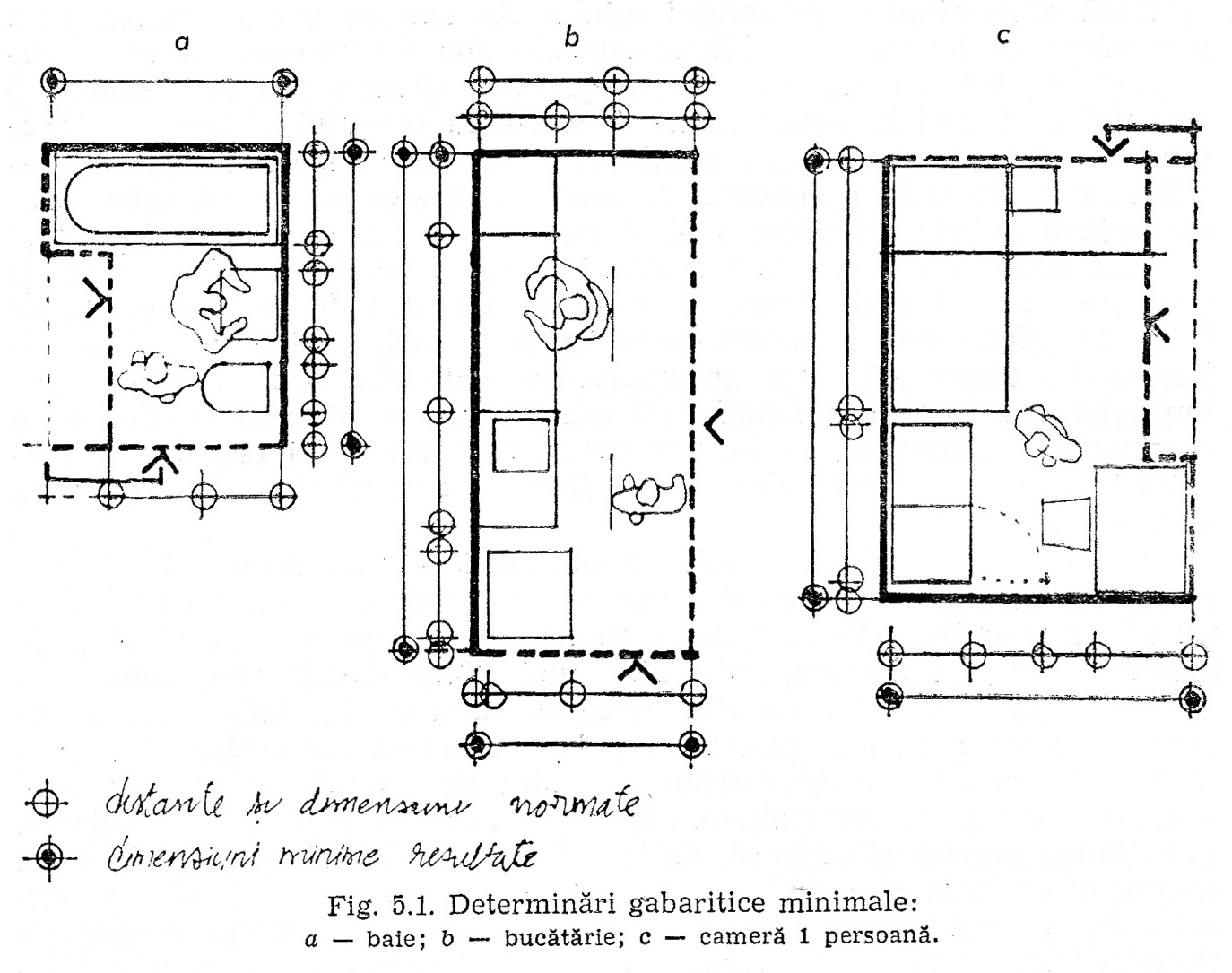

In order to follow the thread of home decorations, I then researched the post-socialist decorations magazines most read by the people I met, among which the most prominent was Casa Lux (1990-present), a trendsetter both in terms of decorations and home installations (such as heating boilers or window frames). I additionally chose to look up socialist technical training books (such as The Book of the Thermal and Phonic Insulator, 1972; Installations in Buildings, 1968) and to use their descriptions and illustrations as starting points for discussions with research participants. Finally, I used Romanian studies of urban transformations, both socialist (Complex Urban Units, 1969; Issues of the Contemporary Dwelling, 1987) and contemporary studies issued by the Faculty of Architecture, Bucharest University. These studies, alongside with Romanian ethnographies discussed later in this Introduction, have not been utilized before in an international setting, as they are written in Romanian and have not widely circulated outside of Romania.