Introduction

A block of flats is both a closed community, which administers the maintenance of the building as a unit; and an open one, related to the functional infrastructure and aesthetic (dis)unity of the city. The introduction sketches how the thesis looks both inwards at processes of maintenance and repair, decoration and refurbishment; and outwards, at wider processes of resource management at the level of the city, the country and the European Union. The introduction also discusses the methodology used, justifying the use of long-term ethnographic fieldwork. Finally, it sets out key theoretical debates that will guide the thesis.

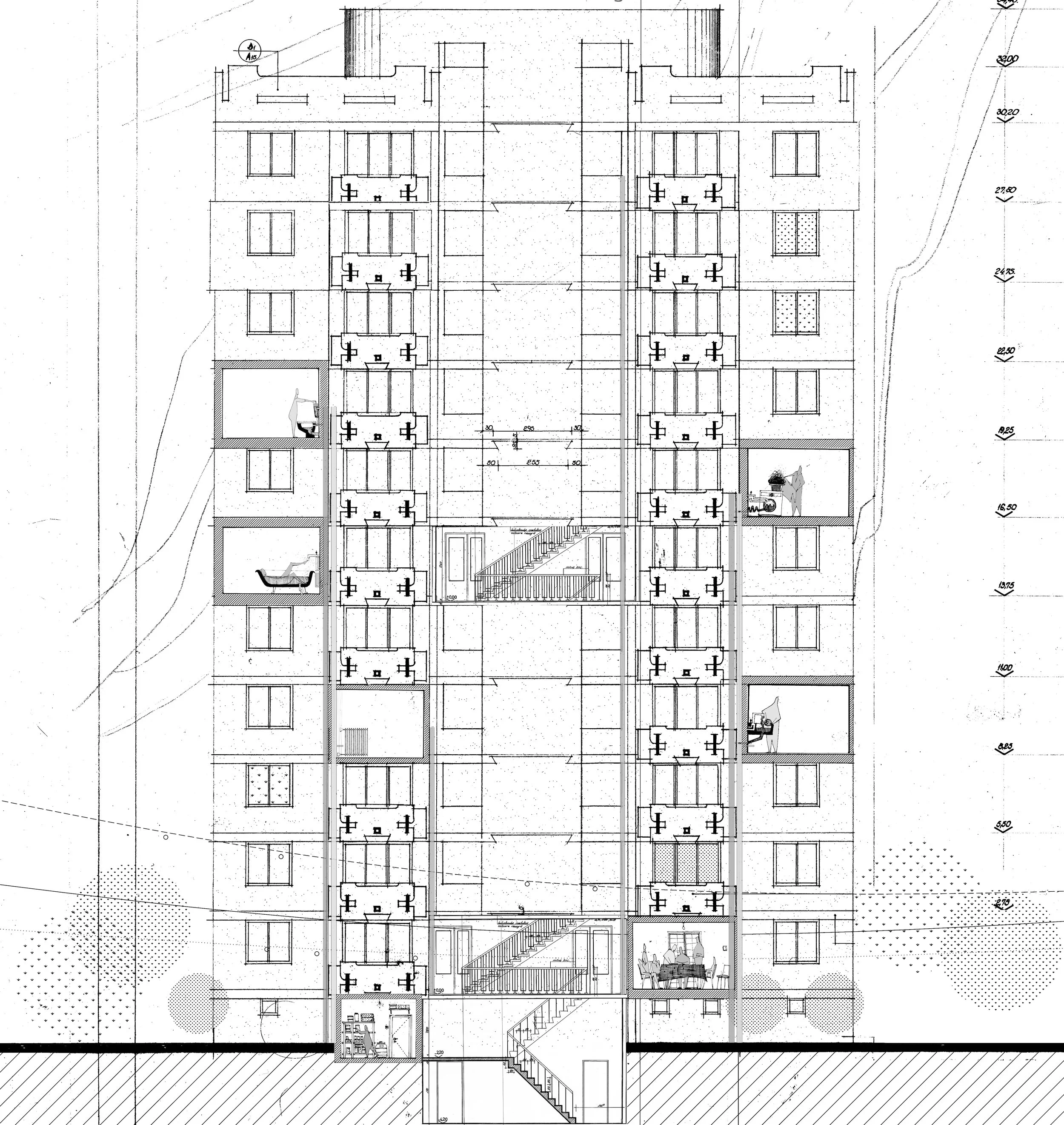

The house and the block

After providing a brief history of the block of flats as a building form, this chapter presents the specificities of the block construction process in 1970s Piatra-Neamt. Swift demographic changes and limited resources led to many flimsy buildings being built very close to one another. Broken taps, bad airways letting through cooking smells, or bad window finishings that allowed the cold air to pass — these were all very common. Therefore, the state required a bottom up system of administration: a way for inhabitants to voice their concerns and organize themselves in the maintenance of the buildings.

The administration room

The third chapter illustrates the administrative dimension of block inhabitation through the lens of Mr. Bud’s activity as a block administrator in H2B. After describing his daily life in the building, from utilities calculations to maintenance work, the chapter describes the inhabitants’ difficulties in paying for their individual bills in good time, leading Mr. Bud to resort to alternative financial strategies to raise money for the block’s maintenance. While these often raise the suspicion of his neighbours, they allow him to maintain the best conditions of the housing fund, while promoting an attitude of respect towards the common property and the moral norms of cohabitation. As such, the block administrator emerges as a key figure of leadership, filling the gap between the state and the market.

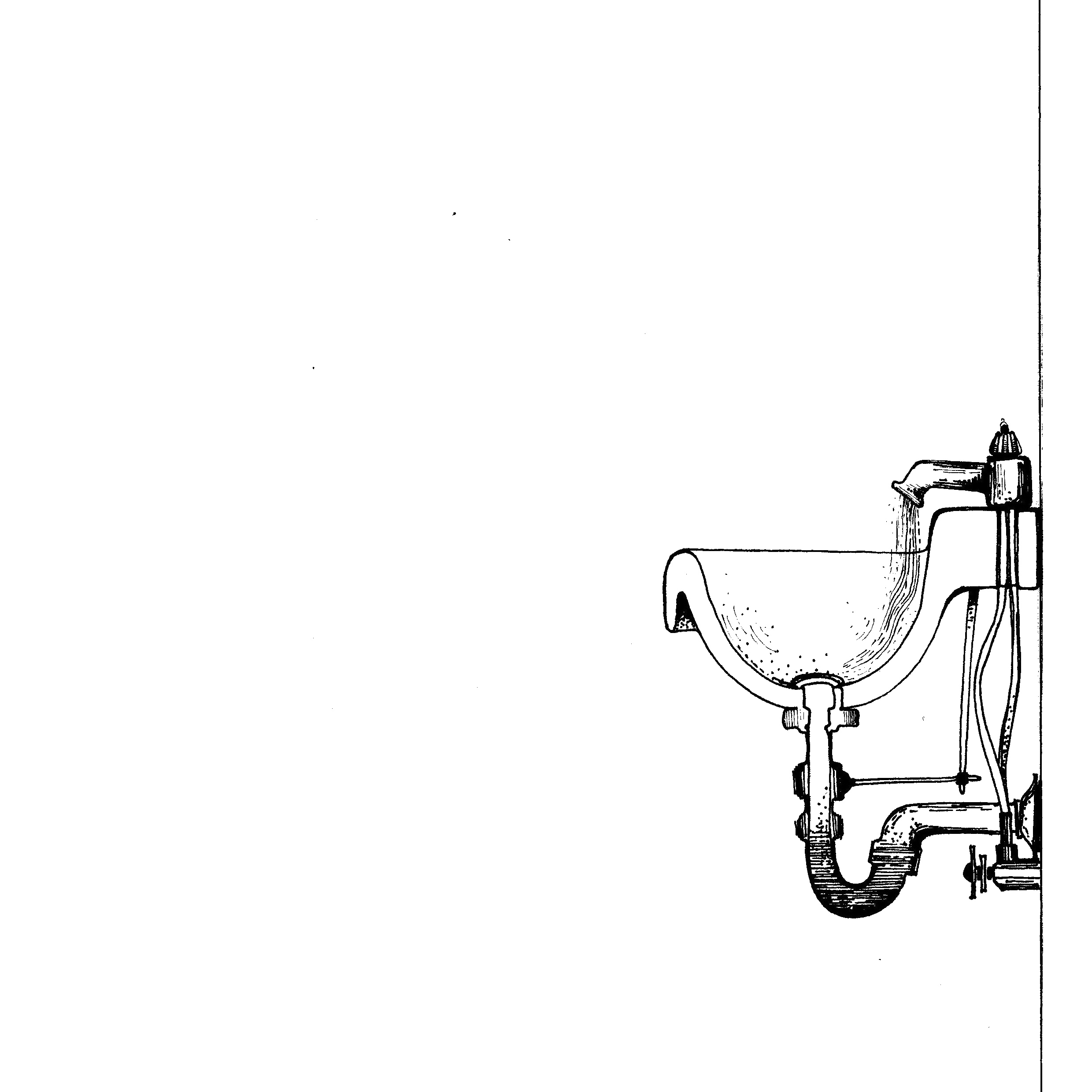

The Water Tap

The fourth chapter explores the relationships of trust and suspicion that are shaped inside the building in relation to water consumption and infrastructure. Faults in the ageing pipework result in neighbours accidentally flooding one another. These moments reveal intricate moral conceptions of what makes a good neighbour: they can both harm the neighbourly relations and create new social relations around mitigating the damage. Additionally, individual water consumption reports, tainted by lies and technical imprecisions, equally shape the social relations inside the block. Conceptually, the relationship between water and the ageing infrastructure is explored through the lens of (1) the building and its apartments, (2) pipes and their corrosions and fissures, (3) residues and their effect on water circulation; and (4) bacteria contaminating the water as it is being transported from its historically clean mountain source. Finally, the chapter draws attention towards a flawed implementation of EU policies of water infrastructure rehabilitation, which has instead lead to higher prices and lower quality.

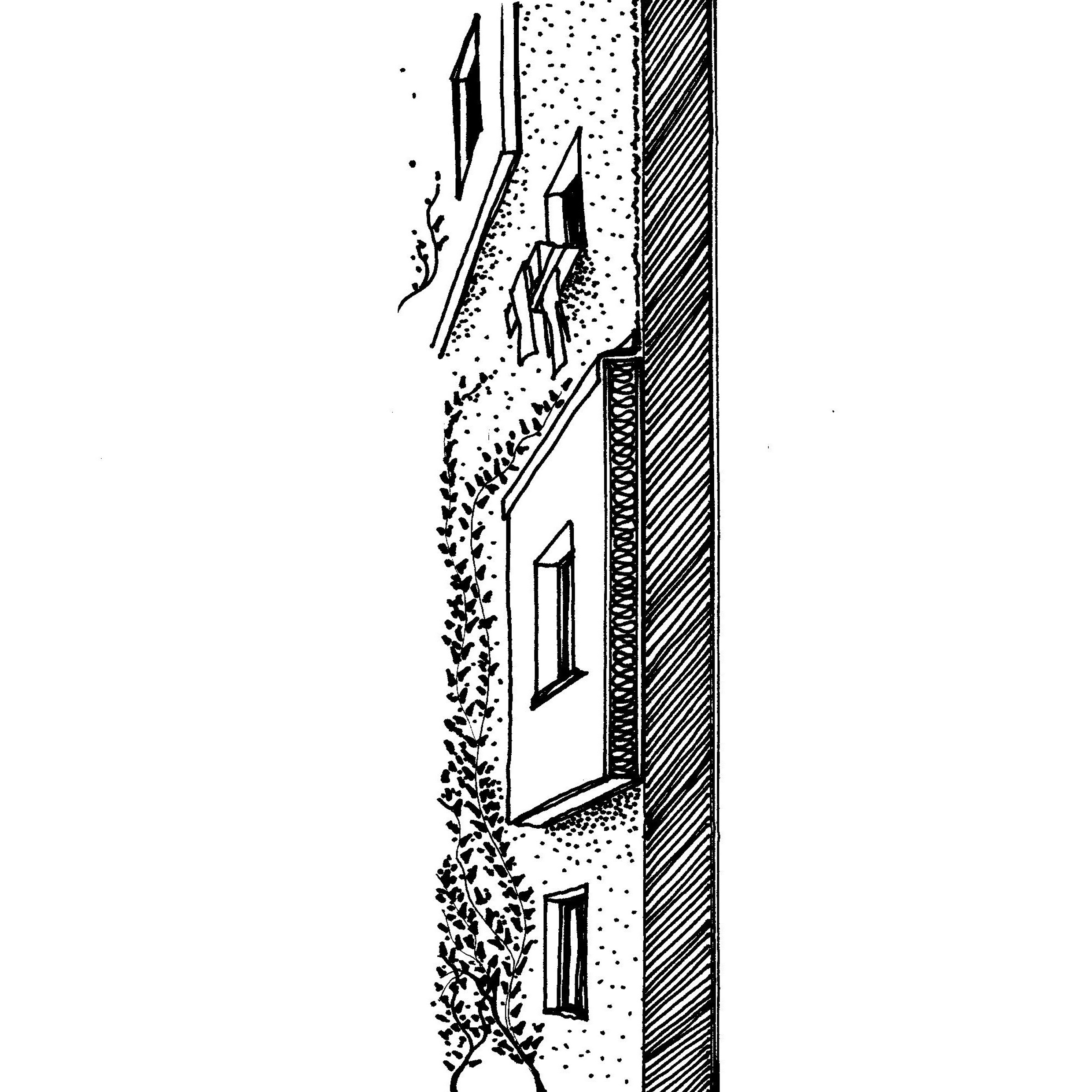

The wall insulation

Another example of an EU policy gone awry is presented in the firth chapter. Indeed, EU funds towards building rehabilitation are often poorly used by the local authorities, failing to reach most citizens who could have taken advantage of it. In the rare cases in which City Hall has managed to thermally rehabilitate some blocks of flats, both sides have taken issue with the process — City Hall have difficulties in retrieving the inhabitants’ contribution, while the inhabitants are frustrated with the low quality and high cost of the work. Unsurprisingly, most inhabitants have had to come up with an ad hoc process of rehabilitation, often insulating independently, without consulting their neighbours. Consequently, the city is drastically transforming into a patchwork of only partly insulated buildings. It is in this context that the example of the H2B block is discussed in great detail, taking into account each step of the insulation process — both financial and technical. Taking achaîne opératoire approach to processes of “making”, the chapter shows the subtle ways in which constructors diverge from the norms of insulation work, eventually leading to a reduction in heating costs.

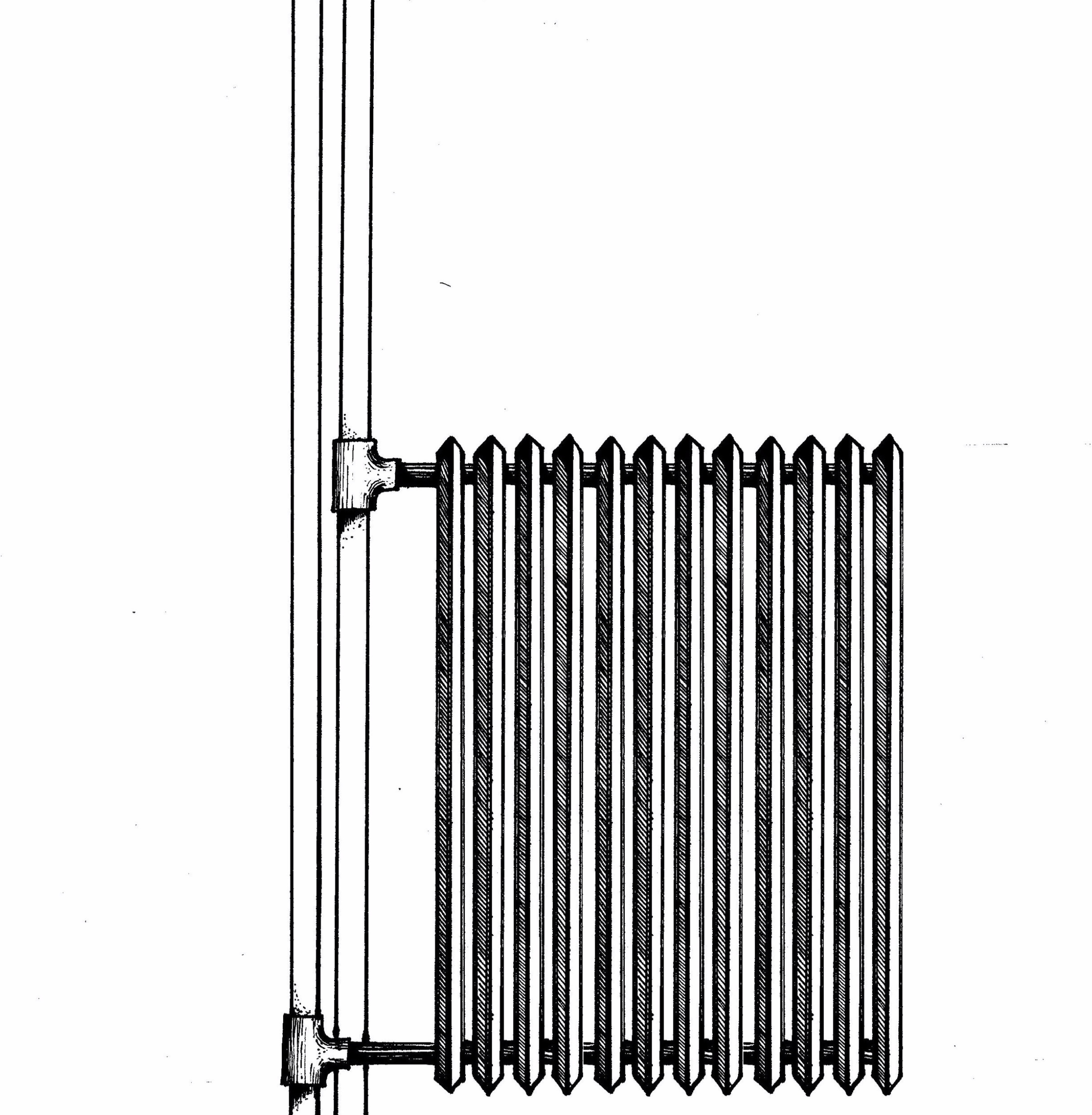

The heater

Because energy saving is at the root of recent rehabilitation work, the sixth chapter looks at heat distribution, and how it has changed from the fully centralised district heating systems, to intermediary block heating systems, to individual apartment boilers. Through the perspective of the H2B inhabitants, the chapter explores the difficulties in maintaining the entire building uniformly warm, despite Mr. Bud’s ardent and well-informed energy saving practices. The chapter follows the complex process of heat decentralisation, eventually leading to ever more fragile systems, lower heat levels and higher prices. Especially for medium sized towns such as Piatra-Neamt, this has led to the proliferation of energy poverty in the harsh climate following the 2008 financial crash. With many apartments empty and cold, and remaining inhabitants only heating the space where they spend most time, principles of thermal balance are often violated, causing energy efficiency issues that can only be addressed centrally.

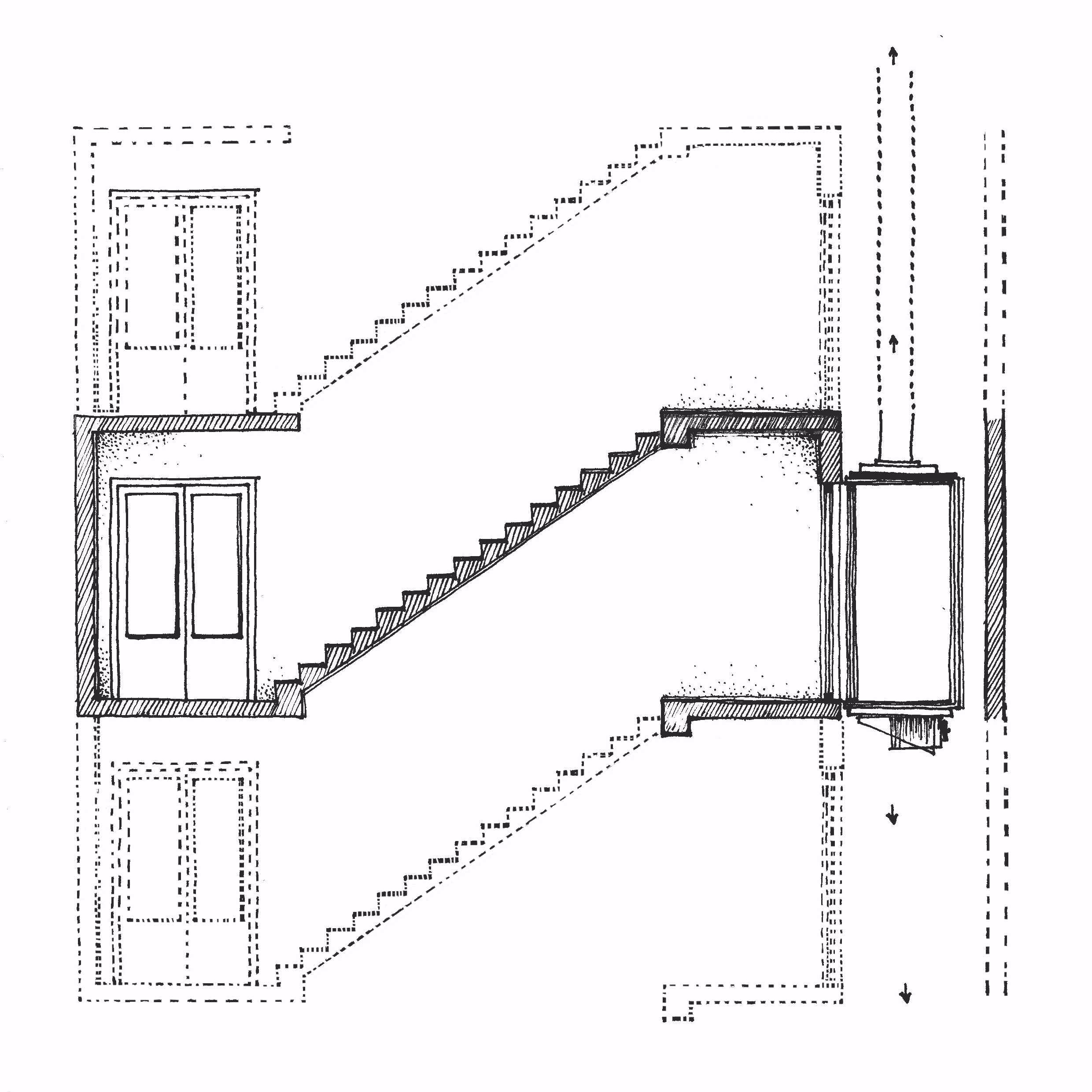

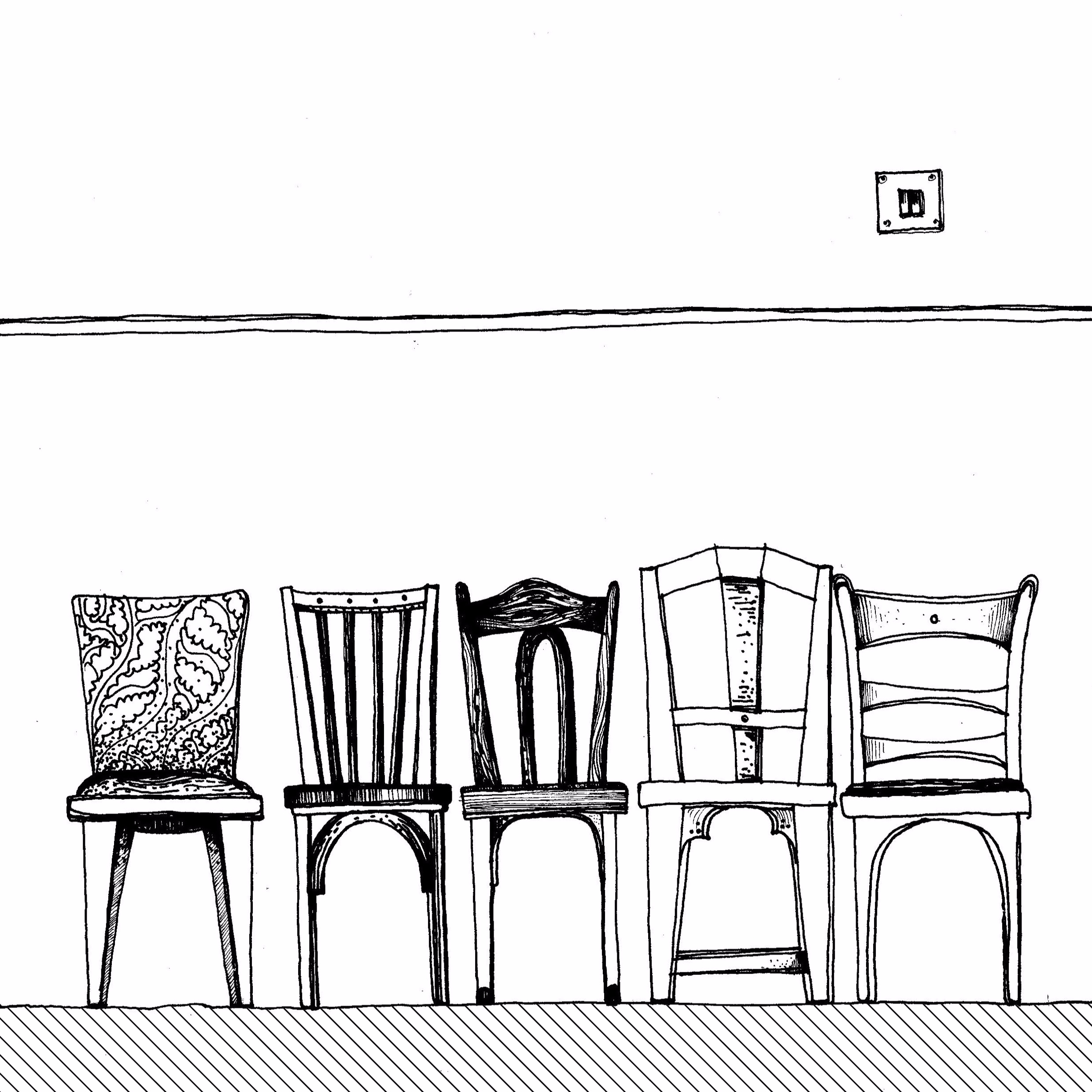

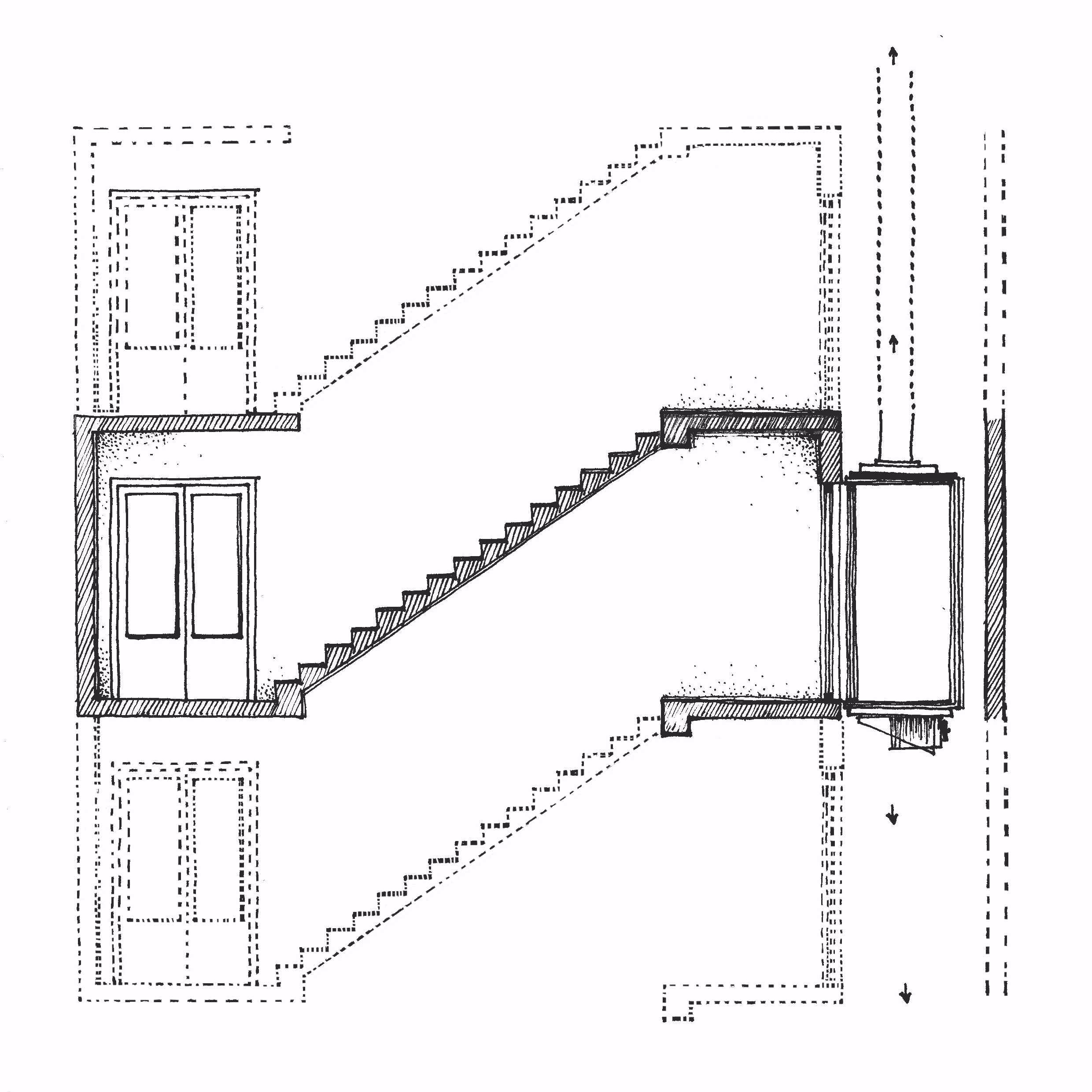

The staircase

The seventh chapter centres on the shared spaces between the apartments, their collective maintenance and their relation to the wider sense of community. The chapter showcases spaces in the building which require careful negotiation, from the entrance stairs and front door, to the elevator and the garbage collection points. The private- public dichotomy turns out to be a messy one, which constantly shifts boundaries. Indeed, the private spaces often “spill” outwards: decorations are moved from the apartments to the common spaces, and garbage invades the staircase, emanating smells or leaving leaky traces as it is carried outside. In order to encourage ‘correct’ behaviour, neighbours use the billboard to pin posters, or the mailbox to leave messages. Following these patterns of communication indicates the criteria by which morality is assigned to the social relationships in the building.

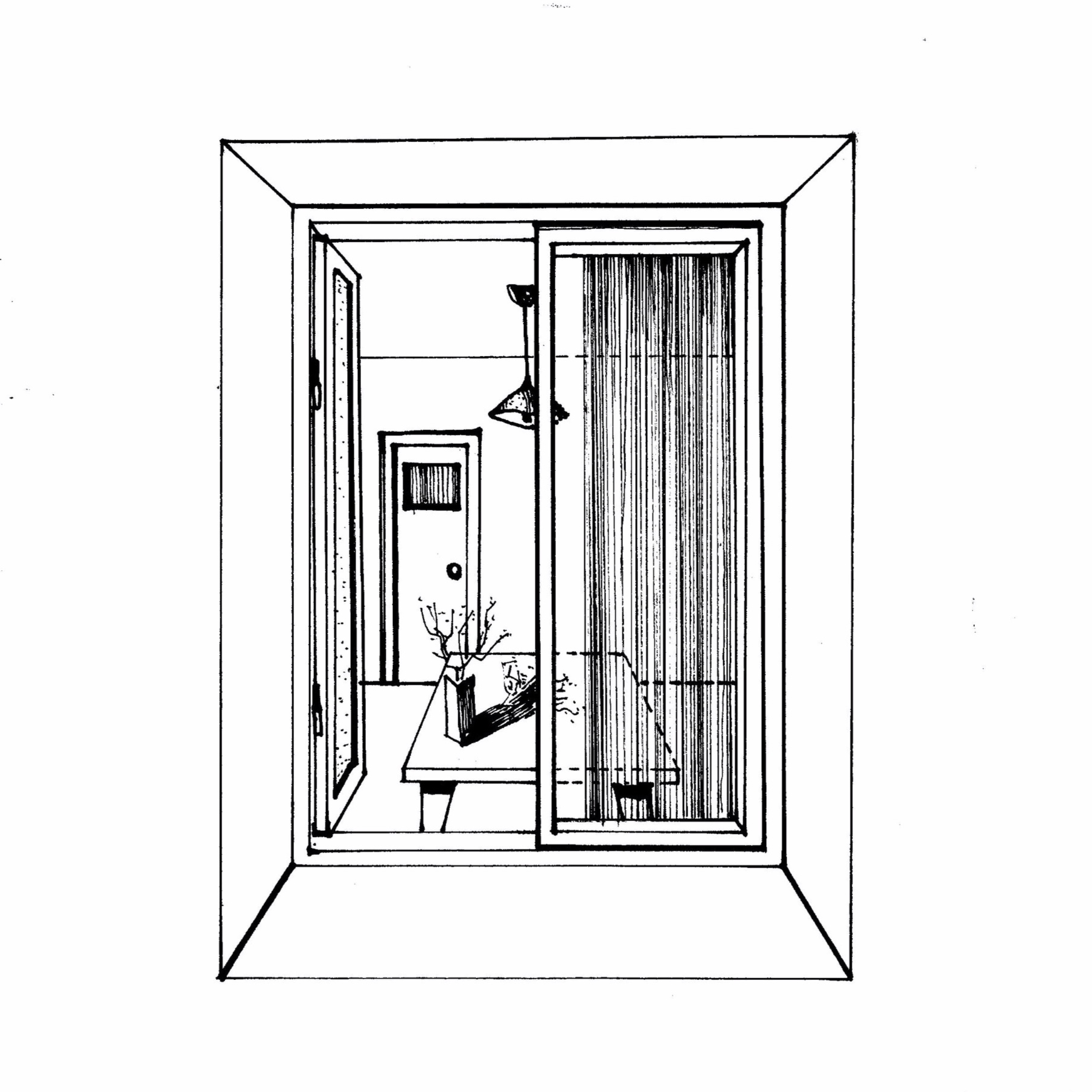

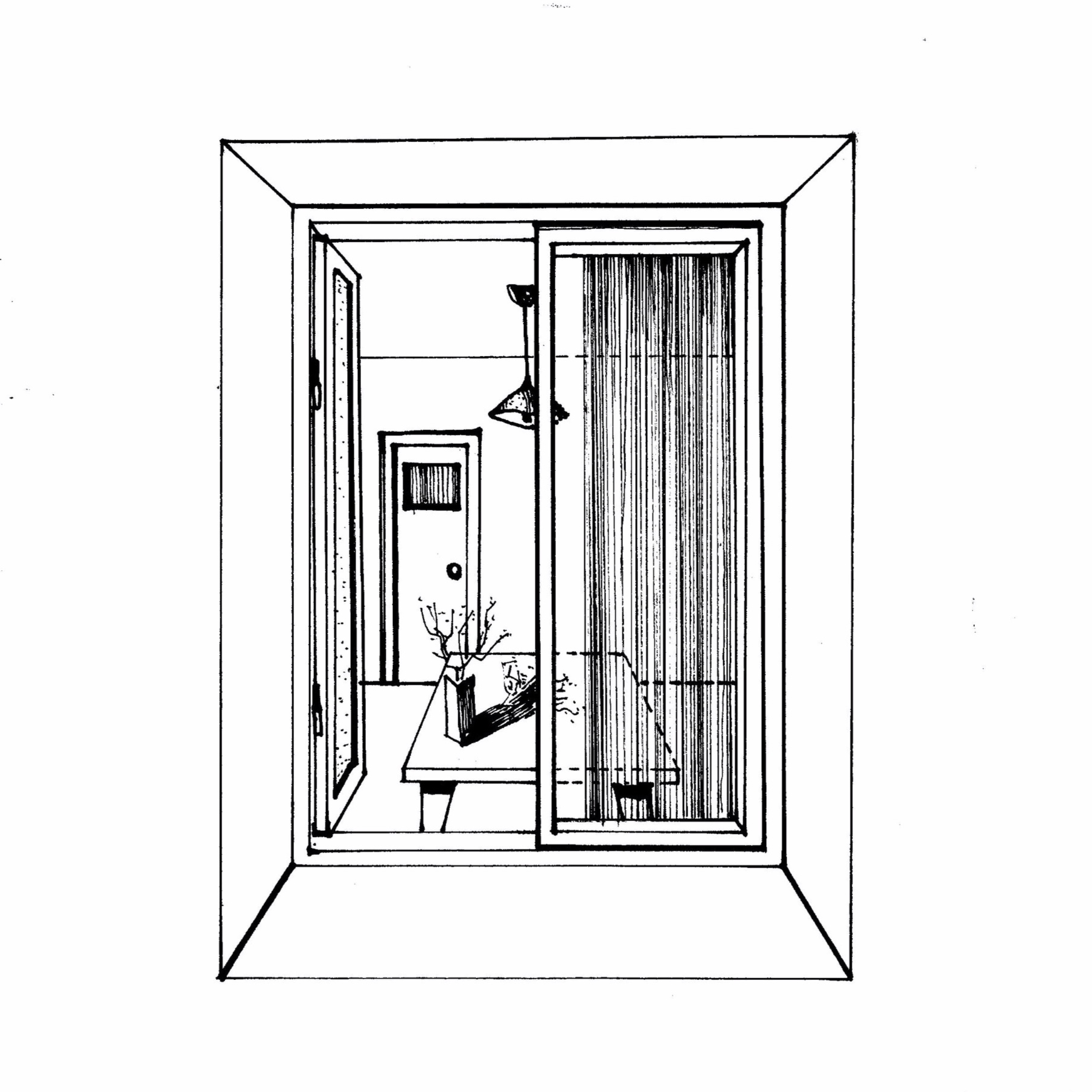

The Window

The final chapter follows the renovation processes aimed at thermally insulating and redecorating the apartments. In order to understand inhabitants’ aesthetic ideals at the same time as the pragmatic manifestations of those ideals, I followed the contents of the decoration magazines used by the inhabitants (especially the women) and their reasoning for interior design changes. Specifically, replacing the wooden windows with double glazed PVC windows is often seen to provide better protection from the harsh conditions of the cold seasons, but it fits equally in discourses of aesthetics, status and modernity. Whereas during socialism, the town administration strictly regulated any home modification that would have an effect on the exterior, during the heat-deprived 1980s, they turned a blind eye to inhabitants’ modifications for energy saving, such as changing the windows and closing the balcony. These changes became evermore common after the change of regime and are currently seen by some as charming ways of appropriating one’s home, and by others as a problematic, “uncivilized” way of intruding into public space. By carefully looking at these modifications, I give an invaluable insight into inhabitants’ conceptualisations of the block and the house.